It’s been 100 years since Prohibition threatened the future of the country’s happy hours and margarita taco nights.

In 1919, the United States of America was going through an identity crisis.

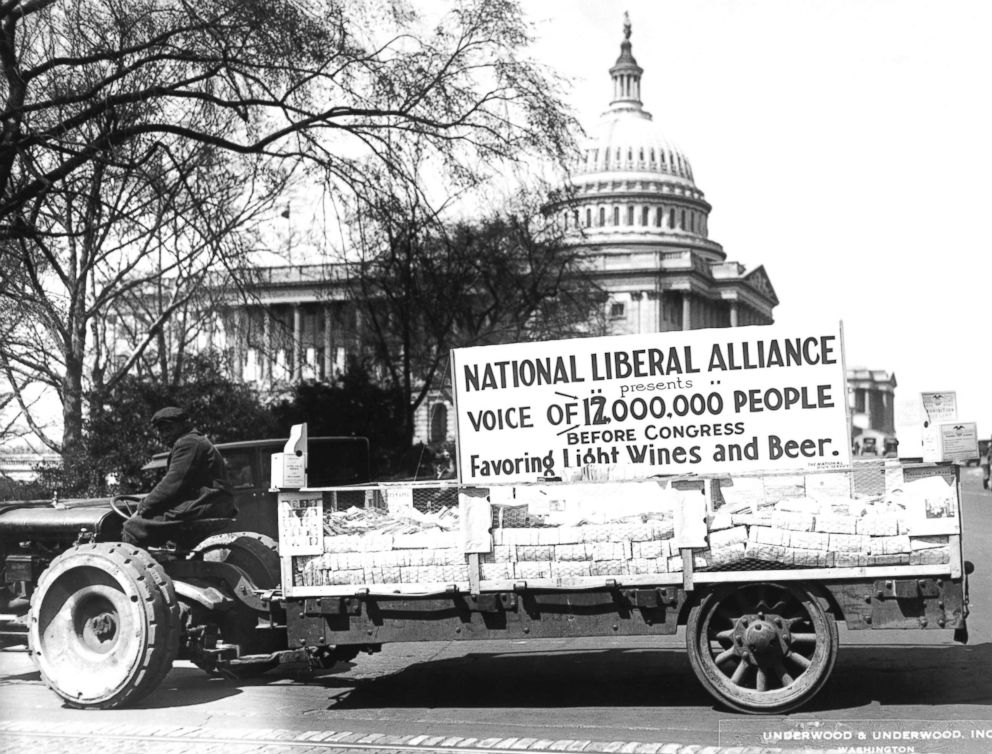

The 18th Amendment, which forbade the making, selling or transportation of “intoxicating liquors,” was ratified on Jan. 16, 1919, and took effect a year later.

Bo Simons, retired wine librarian/historian from the Sonoma County Wine Library, shares the speakeasy’s that sprouted up in Sonoma County in the era of Prohibition and how people were able to enjoy their favorite beverages during that time:

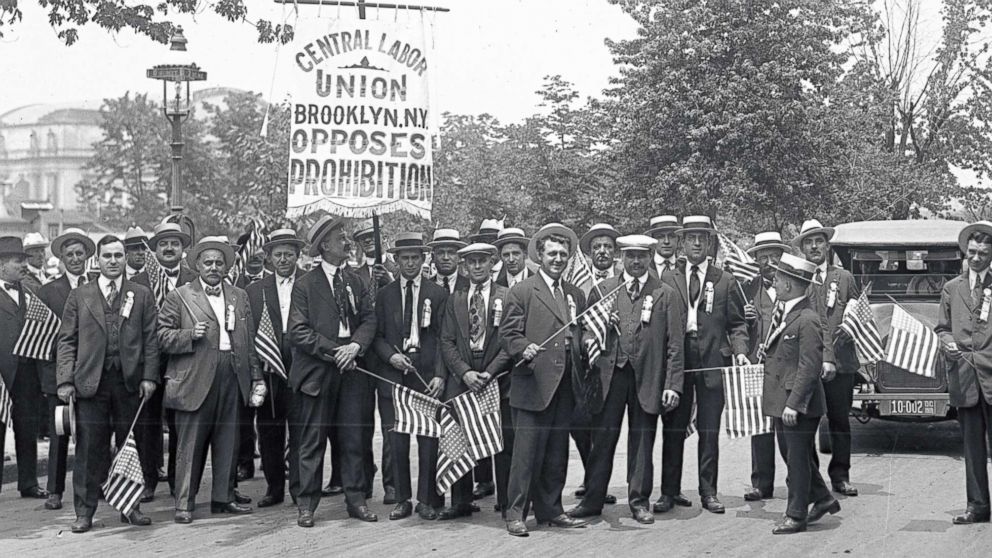

Politicians voted to enact Prohibition as a “noble experiment” to reduce crime, solve social problems, reduce the tax burden created by prisons and poorhouses and improve Americans’ health, according to an analysis on the Prohibition era by the Cato Institute, which characterized the effort as a “miserable failure on all counts.”

The Volstead Act, which went into effect on Oct. 28, 1919, gave states and federal government the ability to enforce the ban via “appropriate legislation,” according to the National Archives.

Even though the 18th Amendment didn’t prohibit citizens from consuming alcohol, it still was responsible for a “major and permanent shift in American social life,” according to The Mob Museum. The consumption of alcohol fell at the beginning of Prohibition, but it increased soon after, according to the Cato Institute.

Many loopholes surrounding the law emerged, and people who wanted to consume liquor had to buy it from licensed druggists for “medicinal purposes,” clergymen for “religious” purposes and bootleggers — or illegal sellers — the museum said in the online article, “Speakeasies Were Prohibition’s Worst-Kept Secrets.”

After Prohibition’s inception, speakeasies flourished. The illicit venues multiplied in urban cities and ranged from “fancy clubs with jazz bands” to basements and ballroom dance floors, according to The Mob Museum. They also welcomed women, ending the segregated-by-sexes drinking of yesteryear, the museum said.

It’s estimated that Al Capone, the leader of the Chicago Outfit, made $60 million a year by supplying illegal beer and liquor to 10,000 speakeasies in the late 1920s, according to The Mob Museum.

Prohibition was repealed Dec. 5, 1933, when the 21st Amendment was ratified, meaning the beginning of licensed barrooms, where liquor and beer is regulated and taxed.

At the time, according to the National Archives, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “What America needs now is a drink.”