iStock

iStockBY: EDEN SMITH

iStockBY: EDEN SMITH

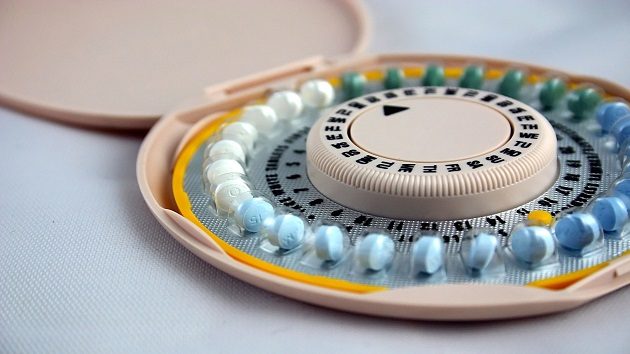

(NEW YORK) — If a woman misses two days of birth control pills in a row, she is at an increased risk for pregnancy.

What if she missed those days because she didn’t have time to refill a prescription?

Dispensing a yearlong supply of birth control pills upfront may be key to both preventing unwanted pregnancy as well as lowering health care costs, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) published in JAMA Internal Medicine on Monday.

“Our motivation is really to improve women’s reproductive health, outcome and autonomy,” said Dr. Sonya Borrero, an author of the study and director of Pitt’s Center for Women’s Health Research and Innovation as well as associate director of the VA’s Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion. “We are suggesting a policy that can do those things and won’t cost the VA money.”

Using a mathematical model based on existing data from the VA health system, researchers found that giving its patients a year’s worth of birth control pills all at once would save the agency $90 per woman per year, a $2 million total savings, and prevent an estimated 583 unintended pregnancies annually.

The birth control pill, formally known as oral contraceptive pill or OCP, is 99.9% effective if taken as directed, according to Mayo Clinic. While OCPs are nearly always written to cover a full year, they’re usually dispensed in 30, 60, or 90-day increments, depending on insurance coverage.

That means a woman must not only remember to take her pill daily, she must also remember to refill her medication and renew her prescription on time. Insurance plans often do not want to supply more than a few months’ worth of OCPs at once, in order to avoid potential pill wastage in case a woman decides to change her method of contraception over the course of the year.

However, Colleen P. Judge-Golden, lead author of the Pittsburgh/VA study, told ABC News that their research proves that “wastage costs would be hugely overshadowed by savings from helping women avoid unintended pregnancies.”

A previous study found that a one-year supply of birth control pills compared to a 30 to 90 day supply reduced the odds of unintended pregnancy among California family planning program clients by 30%, further supporting the notion that a one-year supply of birth control is a more effective dispensing method.

California is among 17 states, as well as District of Columbia, which now give women the option to receive a 12-month supply of birth control upfront.

She believed the VA was the perfect context to examine the implications of a shift to a year-long supply of OCP, since it is the largest integrated American health system. The VA system also shows the financial repercussions of short-term birth control supply — many veterans in the system incur a copay for OCP, and must pay out of pocket for abortion procedures.

“The high prevalence of chronic medical conditions coupled with no abortion coverage makes it really critical that we support these women’s use of contraception when they want to use it,” said Dr. Borrero.

The mathematical model researchers used was based on 24,309 heterosexually active female VA enrollees between the ages of 18 and 46 who did not want to get pregnant for at least one year. The model did not attempt to compare the effectiveness and financial benefits of alternative long-acting reversible contraceptives that the VA also currently offers — birth control pills are the most commonly used contraceptive method in the U.S. The model also did not take into account certain scenarios, such as a woman misplacing her pills, switching to another form of contraception over the course of a year, or the possibility that a woman simply forgets to take her daily pill.

“When we do vary all the variables in the model over all these ranges, this policy is still overwhelmingly favorable in terms of the ability to prevent unintended pregnancies and financial implication for the VA health care system,” said Judge-Golden. “We consider this a win-win.”

The VA acknowledged studying the effects of these policy changes is particularly important as the number of women veterans, especially of childbearing age, enrolling in VA health care increases, but said it isn’t prepared to change its policies yet. “We are interested in this work but it is still unproven,” said Dr. Patricia Hayes, chief consultant for Women’s Health Services for VA Health Administration, in an interview with ABC News.

Dr. Hayes acknowledged the problem of gaps in OCP coverage, and said the VA tries to help women who want to prevent pregnancy with a wide range of options to make it easy to get birth control pills, including phone and online prescription refills.

She added that one of her concerns is that a 12-month upfront birth control supply option has the potential to discourage provider engagement, and weaken the patient-provider relationship.

Judge-Golden disagrees, saying a year-long prescription of birth control pills “should have no impact on patient-provider engagement,” as medication dispensing and refills are separate from patient interactions with their healthcare providers.

“Prescriptions for contraception are nearly always written for a full year, and practice guidelines recommend that women receive well-woman/preventive care visits once annually,” said Judge-Golden.

The study’s authors hope that their model will convince health care providers to give women greater flexibility in managing their reproductive choices.

Rising rates of maternal mortality in the U.S., coupled with a recent wave of laws in various states attempting to curtail access to abortion, underscore the importance for many health care researchers and practitioners of developing easier ways for women to independently meet their reproductive goals.

“We think that this offer is an economically feasible and relatively simple, evidence-based approach to help women prevent undesired pregnancies,” Judge-Golden said of an upfront, 1-year supply of birth control.

Dr. Borrero agrees.

“The impact to their health and mental wellbeing is greater than anything we can ascribe a numerical value to.”

Eden David is a rising senior at Columbia University majoring in neuroscience, matriculating into medical school in 2020 and is a member of the ABC News’ Medical Unit.

Copyright © 2019, ABC Radio. All rights reserved.